Format: Cinema

Release date: 6 September 2013

Distributor: Artificial Eye

Director: Paolo Sorrentino

Writers: Paolo Sorrentino, Umberto Contarello

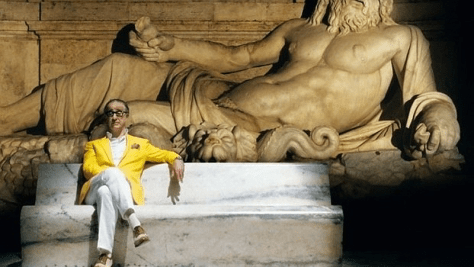

Cast: Toni Servillo, Carlo Verdone, Sabrina Ferilli

Original title: La grande bellezza

Italy, France 2013

142 mins

Certain parallels aside (set in Rome, the passive journalist protagonist, the lavish life-style), The Great Beauty (La grande bellezza) is no simple remake of Fellini’s La dolce vita, although it might ask the same big existential question about the meaning of life in a city that, as it appears in Paolo Sorrentino’s film more than 50 years later, is as dazzling and captivating as ever.

An ageing art journalist, one-off bestselling author and tireless gigolo, Jep Gambardella (played by Sorrentino’s favourite and long-term collaborator Toni Servillo) knows many a secret and the entire high society in Rome, but can’t seem to make sense of his own extravagant life. At his 65th birthday party, his façade of irony and ignorance slowly begins to crumble as he bemoans the lack of ‘true’ beauty in his world of excess, luxury, endless spiel and easy women, and blatantly shares his disgust with his so-called friends and enemies, as much as with himself.

In keeping with the often excessive, ironic visual style Sorrentino introduced in his earlier films, such as Il Divo and The Consequences of Love, The Great Beauty makes for somewhat exhausting viewing, and might seem to some superfluous from the start and preposterous in the execution. But it’s also a beautiful film about loss, death and sacrifice, and about those special, unforgettable moments you share with others that make life worth living.

Pamela Jahn talked to Paolo Sorrentino at the 67th Cannes Film Festival in May 2013, where The Great Beauty premiered in competition.

Pamela Jahn: The Great Beauty has a very dreamy feel to it, but was is meant to be more a nightmare or a day dream?

Paolo Sorrentino: Luckily, or maybe unluckily, it’s reality. It’s a world which is reinvented and revisited through the tools that we have at our disposal but, still, it’s reality.

Much like your main protagonist Jep, you seem to be going through a journey yourself, trying to find out what beauty is.

Undoubtedly, this is true for my work. And I share quite a few things with Jep, especially a sort of disenchanted way of looking at life and searching for emotions. I think that the search for beauty and emotions triggers my desire to make movies, and to express myself in an artistic way.

You talked about reality. Sometimes it feels like these parties Jep strolls in and out of are full of human zombies. To what extent did you want to make a statement about a certain social class and the freedom money gives you to change the way you look?

I don’t seem to be able find any beauty in the transformation of bodies through surgery or Botox, but I didn’t want to make a statement or anything like that. It’s so easy to do nowadays because there is such an abuse of techniques in cosmetic surgery. Nonetheless, I’d like to understand this phenomenon, because behind it there is a lot of pain and sadness, the inability to accept your body and the flowing of time.

You have a long and interesting working relationship with Toni Servillo. Are you worried that one day you will call him to say that the next script is ready and he says ‘no, thanks’?

It’s actually happened once already. I offered him a script and he said no, and that script never turned into a film. I pay great attention to the reaction of actors and producers, and if they say no to something, that might be a warning sign that there is something fundamentally wrong with the script.

What do you see in Servillo that you don’t get from other actors?

He is, of course, a very good and talented actor, and able to give a surprising performance, but this is true also for many other actors. We are tied by a bond of friendship, so there is always the feeling of working with your family when we make a movie together. This is very important for me in terms of feeling supported when embarking on a project.

Another question that arises from your film is whether too much beauty can be paralysing?

Yes, definitely. I think when you are surrounded by too much beauty, as it can happen to you in Rome, all of a sudden you can find yourself feeling lost and unable to find words to express what you see and what you feel.

How do you overcome this fear?

Probably one option is the way Jep deals with it. He thinks that beauty can also be found in the worst things, beneath the surface, in anything that appears ugly from the outside. And because you are not immediately blinded by it, you might be able to describe it.

The city is a character in itself in your film. What kind of Rome did you want to portray and how much did you want to do distance yourself, or create an homage to, Fellini’s films, like La dolce vita and Roma?

In Fellini’s films there was a feeling of easiness and it was a sort of ‘golden age’. There was a void in those films too, but it was then based on excitement and enthusiasm, and the positive energy of looking to the future. Today, you have a void as a lack of that positive energy and a lack of meaning.

Do you think about art in a similar way?

No, I think artistic expression can always find a way in. The difference today lies in our ability to trace these artistic expressions and to find access to them, which is not always easy. Personally, I think that, despite any conceptual or intellectual artistic expression that I might be unable to appreciate, there are still art forms to be found that are connected to feelings and emotions, which are the art forms that I like. In my films, sometimes I use irony when I don’t agree with something, because irony is a great tool to criticise. And Jep does the same, but when he goes to the photo exhibition of the man who takes pictures of his own life every day, he is no longer ironic, because he is touched by what he sees and the feelings that these photographs evoke in him.

Your films are characterised by a very specific style of cinematography. Is it difficult for you to create this kind of look?

It would probably be much easier and more profitable to pay less attention to the visual aspect of the films, and I am often told that I am too excessive in what I do, but that’s the way I like it.

The film is called The Great Beauty but it’s also about death. Are these two things connected for you?

I wish I could find the connection, but so far, I’ve been unable to do so. I would like to find it, because it would be a solution and a great relief for some of the anxieties that we all feel towards death.

Most people also suffer from a feeling of anxiety about getting older, including Jep. How about yourself?

Absolutely. I’ve been afraid of getting old since I was 20, or even before then. When I was little – I must have been 6 or 7 years old – I asked my mother, ‘When do you die?’ She said, ‘When you are 100 years old’, and I started to cry because I thought there was so little time in between.

Is that anxiety something that pushes you to produce more films the older you get? Do you feel that pressure now more than perhaps ten years ago?

No, I don’t so much feel it with regards to my work. I remember something that a filmmaker, Antonio Capuano, once told me, and I thought it was very true. He said, ‘In cinema, or filmmaking, there are only four or five things that can be told’, and I deeply believe in this, so I am only making films about the things that I think I want to tell.

What are these five things for you?

I probably only have a couple to be honest. Five things might apply more to Fellini and Kurosawa and what they have been able to say with their films, not me, really.

Interview by Pamela Jahn

Watch the trailer for The Great Beauty: