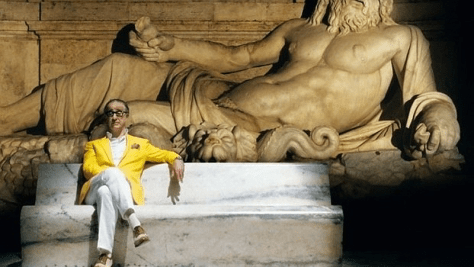

Petey Dammit is an American daredevil who became an icon in the 1970s for his incredible motorcycle stunts. Some of his most famous include riding through fire walls, jumping over rattlesnakes, flying over Greyhound buses, and nearly dying from a launch over the fountains in front of Caesar’s Palace in Vegas. Before becoming a stuntman, he had a greatly varied career in underground music, including such bands as Big Techno Werewolves, Dylan Shearer, The Birth Defects and Thee Oh Sees. He broke 37 bones and one guitar during his lifetime. He is also one of the main characters in Ada Bligaard Søby’s documentary Petey and Ginger. Below Petey picks the 10 films that have most affected him.

1. The Castle (Rob Sitch, 1997)

This movie centres around the Kerrigans, an Australian family who has to fight to keep their home from being taken away by a neighbouring airport expansion. I watched this movie on a flight to Australia the first time we toured over there, and it gave me pretty much everything I needed to know about the amazingness that country had to offer, and I instantly fell in love. Everything about this movie is great and works really well together. The low-budget look of the film and set designs go perfectly with the acting, and the Kerrigan family as a whole. Although it’s a great comedy with constant dry laughs and memorable quotes, I can’t help but tearing up in happiness at the end with the amount of love the family members have for each other.

2. Raising Arizona (Joel and Ethan Coen, 1987)

I think I’ve watched this movie more times than any other movie throughout my life. I could quote it word for word while watching it. In fact, I don’t like watching it with other people, because I know how annoying my ability to speak along with the dialogue must be. There is a pencil sketch of Nicolas Cage hanging on my wall that I bought at a tourist trap here in San Francisco, and I can’t look at it without thinking, ‘My name is H.I. McDunnough… Call me Hi.’ Nicolas Cage is the man!

3. Wristcutters: A Love Story (Goran Dukic, 2006)

This love/buddy/road-trip black comedy is set in an alternate, afterlife limbo designated for people who commit suicide. The main character is distraught after his girlfriend breaks up with him, so he decides to kill himself. As punishment, he finds himself in a new world where everything is pretty much the same as when he was alive, except slightly crappier. For such a depressing (yet extremely interesting) concept, it’s surprisingly upbeat and has a lot of cameos from great people like Tom Waits, John Hawkes, Will Arnett and Eddie Steeples.

4. Festen (Thomas Vinterberg,1998)

Oh man, whenever I try to talk about this movie to friends, I explain that after watching it you will either call your parents and tell them you love them, or you will never speak to them again. This is a pretty heavy film, and the first of the Dogme 95 films. I think this works to Vinterberg’s advantage, because the simplistic nature of the filming and acting make it seem more believable, as if you were there at the party witnessing all the events unfold. I feel pretty gross after watching it, and that’s why it’s one of my all-time favourite movies. Not for that feeling of grossness, but because it makes me feel it so much.

5. Wild Zero (Tetsuro Takeuchi, 1999)

Guitar Wolf, the coolest rock’n’roll band in the world, get a feature-length film that is just as cool as they are! This movie has pretty much everything that you’d need for a Saturday night – zombies, gratuitous blood and gore, UFOs, fire-spurting microphones, hot pants, a transsexual, a naked girl firing guns, and the best takedown of an alien mothership ever put to film! Just watch it!

6. Mother Night (Keith Gordon, 1996)

I’m a big fan of Kurt Vonnegut’s writing, but I can’t think of too many examples where his books have been translated to film with much success. This one is about as good as it can get. Nick Nolte is perfect as Howard W. Campbell Jr., an American-born playwright in Germany during WWII who spews Nazi propaganda that is laced with important hidden messages for the Allies on a radio show. Years later he is living in New York and his former life comes back to haunt him. I find a lot of this movie to be pretty powerful without being cheesy or in your face. It’s great for Sunday afternoon, lying around the house movie watching.

7. Jerkbeast (Brady Hall and Calvin Lee Reeder, 2005)

A friend in Seattle played this movie for us during some down time on tour and it changed my life. Jerkbeast started as a small, public-access TV show where viewers would call in to dial-an-insult the cast (including Brady Hall in a giant, papier mâché monster costume). The cast was known to assault the callers with hilariously foul-mouthed insults at rapid-fire speed. After the TV show ended, they decided to amp up the insults and create a feature out of the carnage. Starting a punk band with many name changes (Blood Butt, Anus Pussy and Steaming Wolf Penis) they hit the road to perform shows for no one, slinging as many insults as possible, such as, ‘I don’t know how I resist the urge to stab you in the face with a frozen stream of horse piss!’ until fame and fortune finds, and then ultimately destroys them. This no-budget (purportedly $5,000–$6,000) movie is perfect for sitting around with your mates getting drunk and laughing until you can’t even sing the words to ‘Looks Like Chocolate, Tastes Like Shit’ any longer. Co-director Calvin Lee Reeder has also made the surreal films The Rambler and The Oregonian, which are also worth checking out if you want to take a drug-free journey to bad acid town. A lot of great clips from the public access show are up on YouTube.

8. Duel to the Death (Ching Siu-tung, 1983)

I love kung fu/wuxia films, and this one has it all. Duel to the Death is from my favourite era of these films, because it was made in the days (and was among the first) where invisible wires and matting worked alongside the martial arts action to create the fantasy style which I greatly love. I generally don’t like CGI-heavy films as they don’t seem real enough for me, or they look slightly off enough that my brain can’t trick me into believing what I’m looking at is real. In this film, a Chinese swordsman is pitted against a Japanese swordsman to determine who is the best, and which nation has the greatest honour. Leading up to this battle, we find that this year’s fight is rigged and no one is to be trusted. The incredible fight scenes aside, this movie features a lot of bad ass ninjas! Kite-flying ninjas, buried-in-sand ninjas, a naked ninja and a fifteen-foot-tall ninja who explodes into multiple ninjas. Why would you not want to watch that?

9. Bunny and the Bull (Paul King, 2009)

OK, I know I just said I don’t like CGI-heavy movies, but I love this movie. The effects create the world within the movie instead of enhancing the world that we know, and it’s amazing. I’m a huge fan of British comedy shows, so finding out this starred many of my favourite people was a treat.

10. Four Lions (Chris Morris, 2010)

Chris Morris, Jesse Armstrong and Sam Bain? I’m there!! I’ve gotten tired of being constantly bombarded with the ‘War on Terror’ and terrorists. It’s frustrating, because I know that those words/phrases are primarily used as a scare tactic to divide our nation and make us afraid of people/cultures that we don’t know or understand, so we will be complacent while the government continues to make the world a worse place by keeping cultures and people apart. The War on Terror is also a great vehicle for continuing a pro-Christian agenda, which also separates society into a hopeless us vs. them scenario. I think Four Lions does a great job of satirising our fears without exploiting any one. Even though the main characters are jihadists trying to kill people, I still want to hang out with them. I still want to help them, and I’m saddened that their plans fail or when they die in the most idiotic situations. On top of it being a great movie, I love it because of that aspect. It’s nice to see a movie where Muslims who are normally portrayed as negative stereotypes are here portrayed as people, who happen to be Muslim. We’re all people, we have different ideas, but that’s what makes the world interesting. Rubber dinghy rapids, bro!