Format: Blu-ray

Release date: 14 March 2016

Distributor: Eureka Entertainment

Director: Luchino Visconti

Writers: Luchino Visconti, Suso Cecchi D’Amico, Vasco Pratollini, Pasquale Festa Campanile, Massimo Franciosa, Enrico Medioli

Inspired by the novel: Il ponte della Ghisolfa by Giovanni Testori

Cast: Alain Delon, Renato Salvatori, Annie Girardot, Claudia Cardinale

Original title: Rocco e I suoi fratelli

Italy, France 1960

177 mins

Visconti’s savage 1960 epic about five impoverished brothers trying to make it in Milan and the woman who comes between them in its fully restored brutal beauty.

Visconti is one of those filmmakers you discover backwards, nowadays, usually starting with Death in Venice and The Leopard. Probably you know, going in, that the maker of these great decadent dramas of luxury and indulgence began as an associate of the neo-realists, dealing with working-class lives. Many find La Terra Trema, his first real effort at social documentation within drama, a touch unconvincing, as if the count from Lombardy was not really too familiar with the world of the poor.

But such doubts disappear in the masterpiece that is Rocco and His Brothers (1960), which brings the epic sweep and microscopic detail of The Leopard to a tale of a family migrating from the impoverished countryside to Milan, seeking their fortunes, and finding, variously, heartbreak, dissolution, enmity, and maybe in some cases, a chance of some kind of compromised happiness. Broken into chapters, each dedicated to one brother in particular, the film takes its time (newly restored, the runtime now reaches three hours) setting up the people and situations who will inexorably fall into the patterns of a tragedy. Chief characters are Simone (Renato Salvatori), the up-and-coming boxer who at first seems the family’s best hope of social mobility, the soft-spoken Rocco Alain Delon), and Nadia (Annie Girardot), their lover at different times. Major stars such as Claudia Cardinale and Paolo Stoppa are placed in relatively minor roles as these three drive events to a shocking conclusion.

This is a fiery male melodrama, in which Nadia, it seems to me, is the most sympathetic character. But as outsider to the close-knit masculine group, she represents in a way the threat of the city, of sophistication and decadent Italian civilisation, and the feminine other. The movie can be read as a warning against the corrupting influence of womanhood, sexual womanhood as opposed to the brothers’ rather stereotypical puritan mama (Katina Paxinou, kind of annoying). But Simone, as far as I can see, corrupts himself, and it’s the access to money and acclamation as well as sex that does it. He’s almost immediately revealed as an arrogant and dishonest character, somehow able to maintain a colossal lie in his head against all evidence: that he is the wronged party in every encounter.

Rocco, by contrast, is a saint, as everyone says. Unusual casting for Delon, who hasn’t flinched from playing some colossal shits in his long career (figures he may identify with to an uncomfortable degree, given his off-screen views and activities). But what good is saintliness, the film asks. Rocco’s attempts to right the wrongs he feels, incorrectly, he has done, result in some of the stupidest noble sacrifices the screen has ever depicted, and his plans take no account of the actual personalities involved. Result: tragedy.

Trapped between the vile Simone and the unworldly Rocco, poor Nadia stands no chance. In one of the film’s most stunning angles, Visconti serves up a Hitchcockian God-shot from the highest pinnacle of Milan Cathedral as Nadia flees her all-forgiving bastard of a boyfriend, running across the rooftop, a tiny speck, like Cary Grant fleeing the United Nations in North By Northwest.

So: if you follow the logic that the truly sympathetic figure is Nadia and it’s really her story, told through the viewpoint of the various brothers, certain scenes may come across as just padding, but you need feel no PC discomfort at the masculine viewpoint, only overwhelming horror and pity. Yes, the film is long, but when it ends, you may wish to start again from Chapter One to see the unspoiled characters once more as they were at the beginning.

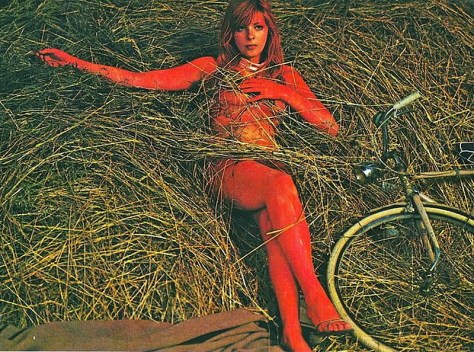

The restoration by Gucci and the Film Foundation brings Giuseppe Rotunno’s cinematography to vibrant life and almost exhausting detail, with the itchy whorls of domestic wallpaper vying for attention with the busy throngs of moving characters. The artful use of light and shade creates b&w images of almost unbearable richness, and the more distressing the story becomes, the more beautiful the imagery. Eureka’s Masters of Cinema series has done the movie proud, with an array of extras gathered from multiple rare sources, including documentary material on Visconti and interviews with his collaborators. My only complaint is the image on the menu, for reasons that will become clear when you watch the film.

David Cairns