Format: Cinema

Release date: 4 September 2015

Distributor: Trinity Film

Directors: Émilie Richard-Froozan, Rémy Bennett

Writers: Émilie Richard-Froozan, Rémy Bennett

Cast: émy Bennett, Evan Louison

USA 2014

96 mins

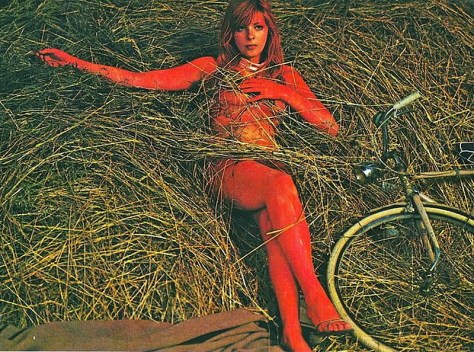

A young girl in a white dress runs out from the woods into a field. Children play games in a hallway, chasing each other, laughing. A girl is spun around in a field, her eyes covered with a yellow strip of fabric. A boy in a cowboy hat stands, smiling, on a wooded path. The meaning of these images is only gradually revealed, but they create an air of tense mystery that persists throughout the striking, compelling Buttercup Bill. Dream-like, elliptical, ambiguous, the debut feature by co-writers and directors Émilie Richard-Froozan and Rémy Bennett is a sun-drenched, erotically charged, Southern Gothic romance about two childhood friends, Patrick and Pernilla, and their cruel, sadistic, yet loving mutual obsession. It’s a film about desperately craving something that you can – and should – never have.

Buttercup Bill starts with the death of a woman named Flora. Pernilla – her friend, her sister, it’s never quite clear – is distraught. Her first act is to leave ‘Patrick’ a phone message, begging for him to come to her. She delivers a poem at the funeral, before descending into a spiral of drugs, alcohol, sex. She wanders drunkenly through neon-lit streets. She leaves more messages. She finds Patrick, finally, in Louisiana, where they’re reunited, their murky past soon inserting itself into the present.

The husky-voiced Rémy Bennett (Pernilla) and Evan Louison terrifically capture the damaged pair, who are like brother and sister, husband and wife, the sexual tension, and jealousy, always palpable. Louison portrays the softly spoken Patrick with a wide-eyed, innocent charm, a good Southern boy. But the problem is that he isn’t good. Or at least not, so he believes, when he’s with Pernilla. Their relationship is intimate, affectionate, yet they continually (especially in one memorable scene) inflict physical and emotional pain on each other, and others. And, as the identity of Buttercup Bill is revealed, and snatched glimpses of the boy and girl become ever darker, it’s clear that their sadistic streak has haunted Patrick and Pernilla since childhood.

In exploring this twisted romance, Richard-Froozan and Bennet have also, refreshingly, if darkly, created an honest, never gratuitous glimpse into female desire. Pernilla is in control of her own urges, an active participant in the games that they play with the people in Patrick’s life – his best friend, a possible girlfriend. A scene in a strip club is seen from the female gaze, Pernilla as fascinated by the dancers as Patrick, Patrick as turned on by Pernilla’s desire as his own. It’s a reminder of just how rare it is to see a film that was not only written and directed, but also produced, by women (Sadie Frost and Emma Comley, and their Blonde to Black production company).

Like the relationship it lays bare, Buttercup Bill is tender, playful, moving and deeply disturbing. It’s beautifully shot, Lynchian in feel, with a vibrant palate imbued with the colours of the south, while the heat of the sun, the moisture in the air, are almost palpable. Although there are definitely moments that feel too staged, too self-aware, the overall originality of the filmmaking, the quality of Will Bates’s atmospheric score, and the sheer forces of nature that are Patrick and Pernilla, make Buttercup Bill a stand-out of the independent scene.

Sarah Cronin

Watch the trailer: