Format: Blu-ray

Release date: 11 January 2016

Distributor: Third Window Films

Director: Takeshi Kitano

Writer: Takeshi Kitano

Alternative title: Fireworks

Cast: Takeshi Kitano, Kayoko Kishimoto, Ren Osugi, Susumu Terajima, Tetsu Watanabe

Japan 1997

103 mins

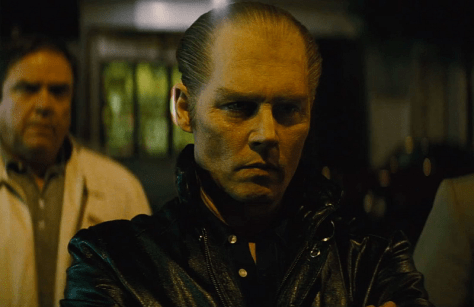

Takeshi Kitano’s 1997 masterpiece wonderfully mixes ruthless violence and heart-breaking melancholy.

Although his international profile has waned somewhat in recent years, the contribution made to contemporary Japanese cinema by the multifaceted media personality and filmmaker Takeshi Kitano remains incontestable. Having directed a unique series of festival hits throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Kitano was perhaps the most internationally successful and visible Japanese filmmaker of the era, at least outside of the J-horror boom. Working in conjunction with Office Kitano, Third Window Films is revisiting this golden age in the director’s career by releasing three newly restored classics, starting with what many consider his best: 1997’s Hana-bi, winner of the Golden Lion at the 1997 Venice Film Festival.

Tender and thoughtful, but punctuated with sudden bursts of ultra-violence, Hana-bi is a wonderful synthesis of the conflicting styles of Takeshi Kitano: the pensive auteur, and his more thuggish screen persona, ‘Beat’ Takeshi. Kitano channels both the brutality of his early directorial efforts, such as Violent Cop (1989), where he plays… well, a violent cop, and the observational sensitivity of quieter works like A Scene by the Sea (1991) or the sorely overlooked Kids Return (1996).

In Hana-bi, Kitano stars as Nishi, a former police officer still reeling from a disastrous stakeout that saw one fellow officer killed and another seriously injured (Ren Osugi). His terminally ill and silent wife Miyuki (Kayoko Kishimoto) is discharged from hospital after the doctors admit that there is nothing more they can do. Owing money to the yakuza, Nishi decides to rob a bank to pay his debt, give reparations to the widow of the slain officer, and use the rest to take his wife on one last road trip before she dies.

Those looking for a slice of straight-up Japanese cops-and-gangsters action may be dismayed by Hana-bi, as ‘auteur’ Takeshi wins out over ‘Beat’ Takeshi. The film moves at a relaxed, contemplative pace, even finding the time to include a secondary narrative focused on Osugi’s character, who, bound to a wheelchair as a result of his injuries, has taken up painting as a means of passing the time. These images seem to offer some sense of accompaniment to the main narrative, which is beautifully realised (the paintings seen throughout the film, incidentally, were done by Kitano himself).

Another aspect that takes precedence over the less salubrious moments is Nishi’s relationship with his wife, who, it’s implied, has not spoken since the unexpected death of their child some time earlier. Despite having hardly any meaningful dialogue, Kitano and Kishimoto form a very strong bond as they quietly visit various tourist spots in rural Japan. Kitano manages to twist the psychopathic qualities of his ‘Beat’ Takeshi persona and imbue his character with a pathos that perhaps first reared its head in Sonatine (1993), but is here fully formed, making his violent streak all the more potent and unexpected. It’s a subtle but marvellous performance from a media personality who, in Japan at least, was perhaps better known for clowning about – see, for instance, Kitano’s extended cameo in his zanily polarising comedy Getting Any? (1994).

That’s not to say that, in Hana-bi, Kitano has shed all humour in the pursuit of serious drama. His wry visual wit is present and accounted for: revelation through juxtaposition; taking the time to follow up on incidental characters after they no longer have any bearing on the narrative (one example being the man who tries to put the moves on Nishi’s wife on a beach and is beaten for his insolence; he is seen later by the roadside, drying his clothes and licking his wounds). Kitano also manages to find the right balance between the overall calm pacing of the film and its short bursts of ruthless physical brutality (including, at one point, some nasty business involving a pair of chopsticks), with the two styles gelling together better than one might expect.

After nearly two decades, Hana-bi remains a high point in Japanese cinema’s renaissance of the 1990s. Despite its (pleasantly) meandering quality, it retains enough toughness to appeal to those coming to Kitano’s body of work from other more genre-orientated contemporary Japanese filmmakers. Naturally, if you’re a Kitano fan, you already know what to do.

Mark Player

Watch the trailer: