Format: Dual Format (Blu-Ray + DVD)

Release date: 2 November 2015

Distributor: Arrow Video

Director: Ulli Lommel

Writer: Kurt Raab

Original title: Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe

Cast: Kurt Raab, Jeff Roden, Margit Christensen, Ingrid Craven, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Germany 1969

106 mins

Produced by R.W. Fassbinder, Ulli Lommel’s take on real-life serial killer Fritz Haarmann is restrained and stylised.

On paper, Tenderness of the Wolves (1973) is an unlikely project, to say the least. The film was produced by legendary German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder, but bears little similarity to his powerful and astutely observed social dramas; it’s certainly difficult to imagine Fassbinder tackling the story of a prolific German serial killer in one of his own films. It was obviously a very personal project for long-standing Fassbinder associate Kurt Raab, who wrote the script and starred as the vampiric, cannibalistic killer. Another Fassbinder contact took the director’s chair: Ulli Lommel, later known in cult circles as the director of the supernatural slasher flick The Boogey Man (1980).

In the wake of World War Two, Fritz Haarmann lives out a comfortable existence, thanks to a campaign of petty crime: fraud, theft, black-market racketeering. He’s a convicted homosexual with a long rap sheet (homosexuality was illegal in Germany at the time), but the overworked and understaffed police turn a blind eye to his activities because Haarmann is a valuable informant. Haarmann himself exploits his police connections by regularly ‘patrolling’ the local train station, which feeds into his secret career as a brutal serial killer who preys on young men and boys, many of them drifters who take shelter at the station. After each kill, Haarmann always has plenty of fresh meat to sell to his friends and neighbours, and give as presents to his police friends.

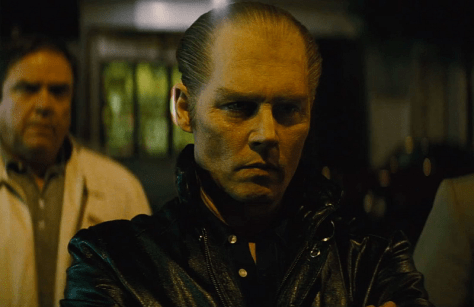

Despite the grim subject matter, Tenderness of the Wolves is relatively restrained. Although violent and bloody scenes do feature in the film’s final third, for much of its length it focuses on a stylized representation of Haarmann’s life and his interaction with others. While it’s clear that he is killing people, the acts are not depicted, just the initial meeting and the subsequent distribution of ‘meat’. This is not without interest, but it does rob much of the film of any tension or suspense, leaving Tenderness of the Wolves left to survive mainly on Kurt Raab’s distant, slightly otherworldly performance. Raab is consistently excellent as the shaven-headed monster, but like the film as a whole, he seems to move at a deliberate and stately pace, as if forced to figure out his every move in advance, step by step. How much enjoyment you derive from the film is largely dependent on your tolerance for its slow pacing, but Tenderness of the Wolves is not without its rewards.

Director Ulli Lommel has had a varied career, to say the least. Born into a showbusiness family, Lommel’s father was a prominent stage comedian who appeared in a number of films in the 1920s and 30s. Like his sister, Lommel took to stage early in life. In the mid-60s he formed a friendship with then-theatrical director Fassbinder. When Fassbinder began moving towards cinema, Lommel went with him, first as an actor, then as a scriptwriter and director. By the late 1970s he had moved to New York and become associated with Andy Warhol’s Factory scene, eventually directing films, including Cocaine Cowboys (1979) and Blank Generation (1980), both of which featured Warhol himself. They also brought him into contact with actress Suzanna Love, a wealthy heiress that Lommel would later marry. Lommel and Love made a series of low-budget horror films together, including The Boogey Man, psycho-thriller Olivia (1983) and witchcraft revenge story The Devonsville Terror (1983), all of which are quirky, interesting takes on standard genre frameworks. From there Lommel directed a series of increasingly dull, anonymous action flicks and TV movies. He resurfaced in the 21st century with a string of zero-budget zombie and slasher movies, most of which showed absolutely no evidence of the talent and ability that Lommel’s earlier films demonstrated.

Jim Harper

Watch the Arrow Video Story to Tenderness of the Wolves: