Format: Blu-ray

Release date: 19 September 2016

Distributor: Arrow Academy

Director: Stuart Heisler

Writer: Jonathan Latimer

Based on the novel by: Dashiell Hammett

Cast: Alan Ladd, Veronica Lake, Brian Donlevy

USA 1942

86 mins

Masculinity is the true focus of Stuart Heisler’s noir tale of crime, power and lust.

Power, corruption and lies are at the burning heart of The Glass Key, with lust adding fuel to the fire. It’s election season, and local power broker Paul Madvig (Brian Donlevy) has unexpectedly decided to throw his weight behind the reform candidate Ralph Henry, turning his back on his own shady interests and his gangster cohorts. The reason: Henry’s beautiful, clever daughter Janet (Veronica Lake), who’s more than happy to take advantage of Madvig’s intentions to help her father’s campaign.

But events are complicated further when Janet’s gambling-addicted brother Taylor, in debt to Madvig’s former partner-in-crime Nick Varna (and also secretly involved with Madvig’s sister Opal), turns up dead, his body found by Ed Beaumont (Alan Ladd), Madvig’s right-hand man. The death becomes a pivotal moment in the power struggle between Varna and Madvig, with Beaumont’s involvement, rather predictably, ensnaring Madvig, Janet and himself in a love triangle. It’s classic noir territory, although Stuart Heisler’s 1942 adaptation of the Dashiell Hammett novel doesn’t quite sit as easily alongside some of the greats from the genre, due to its slow, muddy start.

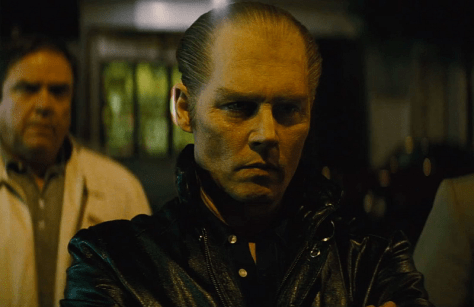

Donlevy plays Madvig as something of a clown, his romantic volte-face derided by his opponents, while everyone seems to know that Janet is playing him for a fool. Veronica Lake is icy in her demeanour, all chiselled cheekbones and glossy, smooth hair, any feelings she has buried beneath her cynical exterior. But The Glass Key is really Alan Ladd’s picture (despite some good lines, Lake is criminally underused in the film). Beaumont comes into his own after Taylor’s death; though initially a suspect himself, he’s canny and connected enough to get himself off the hook, using guile and misdirection to figure out who is behind the murder. But Varna is clever too, sensing blood when Madvig emerges as the most likely suspect.

Everyone is in somebody’s pocket, including the local newspaper owner and the district attorney, with everyone looking after their own skin. It’s these sleazy back-room deals that make the film compelling, the tension increasing as Beaumont finds himself in increasing danger. The Glass Key really picks up after Varna decides to get to Madvig through Beaumont, taking a satisfyingly dark turn that leads to the film’s most explosive and powerful scenes. While Ladd fails in this as a romantic lead, with some wooden acting in his scenes with Lake, and, through no fault of his own, some laughable soft-focus close-ups, he excels as a man fighting for his life. In the end, the most compelling relationship in the film is the one that develops between Beaumont and one of Varna’s thugs, Jeff (William Bendix), who is full of admiration for his opponent’s fighting spirit.

In the end, it barely seems to matter who murdered Taylor, the film more concerned with the themes of honour, loyalty and masculinity. Despite its early failings, there are moments when The Glass Key really shines, with some classic cinematography, plenty of innuendo, and some standout performances, especially from the minor characters.

Sarah Cronin